Tale of Two Pegasi

This is Rainbow Dash.

She is a terrific athlete. That’s why the government of Equestria gave her a very important job. Equestria needs pegasi to help maintain the weather. Farmers rely on pegasi like Rainbow Dash to make it rain when the apple trees need water. Ice skaters rely on pegasi like Rainbow Dash to bring the winter so the ponds can freeze over. Fillies and colts rely on pegasi like Rainbow Dash to bring the summer so the school year can end. The Ponyville marching band relies on pegasi like Rainbow Dash to make it warm and sunny on the day of the parade. Her job is very important. Because everypony benefits from Rainbow Dash doing her job, Rainbow Dash must do her job. Because Rainbow Dash must do her job, Rainbow Dash must get paid. But who pays Rainbow Dash? The pony who makes ice skates is paid by the ice skaters. The pony who makes apple juice popsicles is paid by the fillies and colts. But Rainbow Dash isn’t selling a service to an individual pony. Her work benefits the whole of Equestria, and if somepony is unwilling to pay, she is not capable of excluding that pony from the benefits. She provides a public good, something which is valuable, but neither rivalrous nor excludable. The mechanisms of mutually beneficial market exchange employed by the sellers of ice skates and apple juice popsicles do not apply. Unlike excludable goods, ponies have no incentive to contribute to the process that they benefit from. This is called the free-rider problem, and it’s an example of a market failure.

Market failures are situations when the normal conditions of “optimal” markets, such as clearly delineated property rights, perfect competition, and perfect information, are not met, and therefore non-market solutions, typically state interventions, can create pareto improvements. A pareto improvement is a change in the distribution of goods such that at least one pony is made better off, and nopony is made worse off. The first theorem of welfare economics states that if all goods are distributed under “optimal” market conditions, there can be no further pareto improvements.

Princess Celestia knows how important it is for Equestria’s weather to be properly maintained, so her government allocated a portion of tax revenue to pay for a national service that employs skilled pegasi, including Rainbow Dash, to maintain the weather of Equestria in the way most beneficial to the common good. This means that ponies in Equestria pay a slightly higher amount in taxes, but they all receive benefits from the improved weather that exceed the costs. Everypony benefits, and nopony loses. Thus, the market failure is corrected, and the economists breathe a sigh of relief.

This is Fluttershy.

She is the kindest and most gentle pony in the whole wide world. That’s why the government of Equestria gave her a very important job. Wild animals in Ponyville, just like wild animals on Earth, often suffer from disease and malnutrition, become injured in their daily lives, or become trapped and unable to free themselves. Fluttershy is one of the many ponies in Equestria who takes care of sick and injured animals. She provides vaccinations for rabies and tuberculosis, rescues trapped animals, and provides temporary medical care, food, and shelter for animals recovering from injuries.

Fluttershy’s job is very important. Countless animals rely on her to give them relief from the barbarities of natural life. Because they lack the necessary cognitive capacities to participate in pony society, and as such they do not have jobs, many of the needs of non-pony animals can only be met by ponies, who are endowed with the unique ability to understand and palliate the suffering of others, and as such have a responsibility to do just that. Because Fluttershy has a responsibility to do her job, Fluttershy must do her job. Because Fluttershy must do her job, Fluttershy must get paid. But who pays Fluttershy? Pinkie Pie makes cupcakes, and she is paid by the ponies who purchase her cupcakes. Rarity makes dresses, and she is paid by the ponies who purchase her dresses. But Fluttershy is providing a benefit to customers who cannot pay her. The market, with its system of mutual exchange, will not provide Fluttershy with the incentive to perform her responsibility, and so an intervention is needed.

Princess Celestia knows how important it is for the non-pony animals of Equestria to be vaccinated and have their injuries treated, so her government allocated a portion of tax revenue to pay for a national service that provides care to animals. Some ponies now pay a little more in taxes, but the lives of non-pony animals are significantly improved. This is not a pareto improvement, as some ponies have been made worse off than they would be in the counterfactual, but it is nevertheless desirable, because the benefits to the non-pony animals exceed the costs to the taxpayers.

Both of these pegasi have been employed by the government to perform necessary duties that a free market would not provide. In both cases, the market does not provide goods that would be desirable to provide. However, the situations are different. Rainbow Dash is employed to resolve a market failure, an instance when the market is unable in practice to achieve the distribution that it would in theory. Fluttershy is employed to resolve what I will call a market misalignment, an instance when the theoretical distribution provided by a market would be dispreferable to some other possible distribution. In both cases, an institution outside the market, such as the state, can interfere in the market to resolve the issue.

The phrase “market failure” is often used in vague and confusing ways that distort or misrepresent its primary definition. Sometimes inequality is described as a market failure. This is an inaccurate description. Inequality is an example of a market misalignment, a way in which the operation of a market may result in suboptimal outcomes. It is fundamentally different from a market failure, which is when real world markets fail to meet the conditions of ideal markets. The confusion is not helped by the language often used in economics. “Optimal”, “ideal”, and “perfect” are all words that have wildly different meanings in common parlance than they do in economics.

Market failures are widely discussed by progressive economists. They are frequently used as a means of critiquing laissez-faire and free market ideology, as these systems are poorly equipped to deal with market failures. Market misalignments, on the other hand, are more rarely discussed, despite being probably more important avenues of criticism towards laissez-faire.

I did not originate the concept of “misalignment” in the economic context. Many rationalist-adjacent left-wingers have independently invented the idea. @Max1461 refers to “humanist concerns” about capitalism as “the alignment problem as applied to economic systems.” Other people with views critical of capitalism have raised essentially the same idea, comparing the consequences of the profit motive to the problem of aligning artificial intelligences. Someone on the effective altruism forum made this comparison to argue for a new economic system (they didn’t say which one). Another person on the effective altruism forum made this comparison, but to defend the idea that AI alignment would be easy.

For all the gesturing at the concept of an economy being “misaligned”, I have yet to see an effort to formalize an analysis of market misalignment. This post is my attempt.

This is you.

You are an omniscient and immortal demon from Tartarus with a single-minded dedication to exactly one particular goal: you want Equestria to contain as many paperclips as possible. You do not place any inherent value on anything else, only paperclips. You do not, by the way, represent AI, in case you were under that impression. You are a thought experiment to help the audience understand the concept of social welfare functions. Moving on. You have recently acquired all property in Equestria through a long series of highly lucrative voluntary transactions. All land, natural resources, and capital belongs to you. The only thing that does not belong to you is the labor-power of the ponies within it, who remain entitled to self-ownership.

You consider how you want to utilize the resources at your disposal. Because you are omniscient, you can predict in advance with perfect accuracy how many paperclips a certain timeline will contain if you pursue a particular policy. You call this number P. At all times, you want to pursue the policy that will result in a larger P.

Right now, ponies in Equestria are producing all sorts of things, very few of them paperclips. Some ponies are producing ice skates, others apple juice popsicles, others socks. They are all getting paid to perform this work, but the money they are paid with belongs to you. When I said earlier that “the pony who makes apple juice popsicles is paid by the fillies and colts who buy them”, that wasn’t actually completely accurate. The fillies and colts pay some amount of bits (bits are the currency of Equestria, in case you didn’t know) to the cashier, and the cashier gives them their apple juice popsicles, but even though they gave the money to the cashier, the cashier doesn’t actually own it. When it leaves the hooves of the fillies and colts, those bits now belong to the store owner, which in this case is you. Some of these bits are distributed to the cashier, some to the ponies who make the popsicles, some to the ponies who grow the apples, some goes to the landlord who owns the store (which in this case is you), some goes to the government, and some goes to the shareholders of the business (you again) as dividends. You have no competition, and so you have absolute authority over how this money is distributed.

You can think of yourself as the emperor of a palace economy. Every time somepony pays for something, it goes into your pile of money, and from that pile of money, you can distribute out to whatever location you desire. There need not be any necessary relation between where the money came from and where the money is going. It all comes into the same pile and comes out of the same pile. You are totally neutral as to how a bit enters the pile, but when it leaves the pile, it absolutely positively must go to the location which will result in the highest value for P.

For starters, obviously you need to send some money towards the workers at the paperclip factories. Then you also need to send some money to the workers who mine the iron ore, who refine it, who smelt it, who transport the ingots, and who build the factories and trains and automated machines. But if you were to leave your distribution finished at this, you would have a very small value for P indeed. If the only thing your economy produces is paperclips, then it doesn’t produce anything anypony could buy, so no money would actually be going into the pile. Even if you could appearify money out of thin air, it still wouldn’t make a difference. You still wouldn’t have appearified the things that money represents. Workers could not be incentivized with money that can’t buy anything. The reason workers at the paperclip factories make paperclips at all is not because they, like you, have a passion for paperclips. They do it because they have passion for other things, and, although they are not omniscient, they are intelligent enough to correctly predict that receiving money will place them into a timeline where they will have more of the things they have a passion for. You can’t make paperclips without labor, and you can’t make labor without the kinds of things ponies are willing to trade their labor for.

So you send some money to the apple farmers, the sock knitters, the lumberjacks, the construction workers, the grocery store shelf stackers, and everypony else who is necessary for the production of things ponies desire. You need apples and socks and apartment buildings to incentivize the paperclip workers to work, but you also need them to incentivize the apple farmers to work. This means that the apple farmers and the like are producing enough for themselves, as well as a surplus that goes to the paperclip workers. All of the things they produce are represented by money, so this means that money that leaves the pile for the apple farmers returns to the pile as a greater amount than what left. Otherwise you have wasted bits. So, how does this happen? How can you spend money to receive more money in return? Nopony would ever sell you two bits for one bit, but that seems to be exactly what’s happening. Where are these bits coming from? To understand this, we will enlist the help of the CMC.

This is the CMC.

“That’s right!” says Applebloom. “We called ourselves the CMC because of our passion for the exchange of commodities in the marketplace by means of currency! Our name stands for:

Commodities-Money-Commodities

We used to bring sheets of linen to the marketplace, sell them for their market price, then use the money to buy other commodities at the marketplace. In this way all parties increased their subjective utility and mutually benefited, even though the amount of material wealth in Ponyville was the same as it was before the transactions occurred. So long as we didn’t consume the products we ended up with, we could theoretically sell them for the same price that we purchased them for, and buy back all of our linen, and have the same amount we started with. If we ended up with more money at the end than we did at the beginning, it could only be because somepony else lost money. The economy of the marketplace was zero-sum. Nothing new was created.”

“But then we discovered something awesome!” says Scootaloo. “One time, after selling our linen, we got distracted by an epic adventure and forgot to buy anything at the market. We had wanted to use our linen money to buy dresses. We needed dresses because there was this… it doesn’t matter. The important thing is that I had the idea to ask Sweetie Belle’s sister Rarity to make us dresses.”

“But she wouldn’t do it unless we paid her!” says Sweetie Belle. “So we gave her some linen, and some money, and she made us some dresses out of our linen. But we didn’t end up wearing them because-“

“That doesn’t matter!” Applebloom comes in again. “The important thing is that we sold the dresses, and we somehow ended up with MORE money than we started with at the beginning! The circulation wasn’t CMC, but rather:

Money-Commodity-Money*

Or, MCM*, with the asterisk symbolizing that the final amount of money was higher than the first. We gave Rarity ten bits, and fifteen bits worth of linen, and received three dresses, which sold in total for thirty bits! Five bits came out of nowhere! At first I thought somepony at the market must have been stolen from, but each step of the way we bought and sold at market price. So I thought we must have stolen from Rarity. But when we talked to her…”

“She had more money than she started with too!” says Sweetie Belle. “She still had the ten bits we had given her. And that’s when we realized where the money had come from. Labor is no ordinary commodity. You can’t profit in a fair market by buying linen or dresses. You can only break even unless you steal from somepony else. But if you purchase somepony’s labor power, they can produce more value. When labor is a commodity, the economy is positive-sum! Rarity created fifteen bits worth of value that didn’t exist before, and that wouldn’t have existed unless we had paid her. The price of her labor-power was ten bits, which means that the extra five bits were surplus value.”

“That’s when we realized that all profit is inherently exploitation!” says Scootaloo. “Since only labor produces economic value, the capitalist class serves no purpose in society other than to appropriate the surplus value of the proletariat. Capital is undead labor that sucks the blood of living labor, and lives more the more it sucks! From that day forward, we dedicated our lives to the overthrow of the bourgeoisie and the toppling of capitalist class relations by organizing the proletariat through a vanguard party guided by the immortal dialectical science of marxism-leninism!”

“Class struggle crusaders forever!” They all yell in unison, and run out of your palace, knocking over every trash can on the way. Ah, foalhood. You remember those days, before you had read enough wikipedia articles and blog posts to render you omniscient. In time, they’ll learn about the marginal revolution and the heterogeneity of labor, but for now, you feel no need to spoil their fun, mostly because doing so would not increase P.

Their theory of value will not survive closer examination, but they have nevertheless provided you with a useful framework for explaining the relationship between the palace and the non-paperclip workers. Some commodities, like labor-power, are productive. Well, clearly not all labor-power. Your paperclip makers aren’t netting you any money. Only labor-power that produces things that ponies are actually going to buy is profitable. We can treat all your productive workers as their own class, which produces some quantity of revenue, some portion of which is returned to them. The bits which go to paperclips are “surplus value”, and you the paperclip demon want to set the rate of exploitation so as to maximize surplus value. A 100% rate of exploitation would mean that the productive class is not getting paid, and they would produce no surplus value. A 0% rate of exploitation would mean that the productive class is getting paid everything, and there is also no surplus value. The P-maximizing rate is some number in between, and probably different for each individual employee.

This rate is not constant, but changes over time. If you the paperclip demon are smart, it will increase over time. Of the many things towards which you will be sending money from your pile, one will be labor which increases total factor productivity, such as the development of more efficient machinery and labor-saving techniques. If your employees invent a new machine that can make paperclips twice as fast as the old one, you can increase P without increasing the rate of exploitation. If your employees invent a new machine that can construct houses twice as fast as the old one, your productive class is more productive, and you can re-allocate some workers away from building construction and towards paperclips. The remaining construction workers are producing the same amount of profit as before, but there are fewer paychecks to pay. The same amount of money is entering the pile, but less money is leaving. The rate of exploitation has been increased, but incentives have remained unaltered. The construction workers were already content to work at the wage you provided them. There is no reason to raise it just because you can. Distributing more money to the productive class has diminishing returns. More knick knacks and fancy dinners for your workers is only likely to increase your workforce if you have competition, which you don’t. In your case, it might decrease your workforce, since if they have enough money, they might be comfortable retiring! The ideal endgame for you is that the entire productive workforce consists of one pony operating a machine that produces food, shelter, and clothing for the entire rest of Equestria, and everypony else in Equestria is working at the paperclip factories in exchange for the right to enjoy the fruits of the machine. The rate of exploitation is 99.9999999%, but as long as you have no competition, the economy can continue to be P-maximizing, rather than what some other demon might do with the same productive forces.

You wake up from your wonderful dream. Alas! You knew it was too good to be true. In the real Equestria, you are merely a lowly paperclip-maximizing imp, a far cry from an omniscient demon. You try to tell your economist friend all about your dream, but he doesn’t seem very happy about it. He tells you that the whole economic order you described was one big market failure. Specifically, a monopoly. In an optimal market, there would have been competition. Wages would have been higher, and prices and rents would have been lower. The paperclip demon’s monopoly over production meant that goods were overpriced, and his monopsony over labor meant that labor was underpriced.

“I don’t care,” you say. “In an optimal market, P would have been much smaller. I don’t see why I should want an optimal market. If wages were higher, they’d spend those wages on gold-plated ice skates, and I’d be sending money from my pile to skate-makers that could have been going to more paperclips!”

The economist is puzzled by this. In defiance of all that is holy, this imp seems to be worshiping rent-seeking. Doesn’t he know that rent-seeking is bad? Nevertheless, his argument seems to be correct. If your value system consists entirely of maximizing paperclips, an optimal market is not actually a particularly desirable form for an economy to take. In fact, considering that ponies almost never buy paperclips (no fingers), it doesn’t even come particularly close. It would be trivially easy to think of a government intervention which would result in superior outcomes (from the perspective of a paperclip maximizer) compared to a free market. Putting an excise tax on staplers for instance, and using the revenue to pay for a government program to manufacture paperclips and bury them underground. Even without the omniscience of the paperclip demon, one could be pretty certain that this would increase P.

And there’s nothing special about paperclips. An omniscient demon could organize all of Equestria around maximizing toothbrushes, horseshoes, ammonia, romance novels, or apple juice popsicles, and it could in each case vastly outperform an optimal market according to its own arbitrary measure.

But this is hardly a point against the free market if one has a value system even tangentially related to meeting ponies’ desires, rather than producing arbitrary knick knacks to be buried in the ground, reasons the economist. The market performs a whole lot better from the perspective of a value system which values providing ponies with the things they want, which is precisely what a market does! The CMC may decry capitalism as evil, but if Applebloom wants a chocolate chip cookie at 3 AM, there will be somepony in Ponyville to provide it for her. Not because the cashier or baker or landlord or company CEO are omniscient cookie demons, but because they know some ponies will be willing to exchange money for cookies. It is as if her hunger for cookies traveled back in time to convince hundreds of ponies to work together to build a store which could later sell her one at an astonishingly low price in the present. No goodwill between Applebloom and anypony at the cookie company was necessary. Just the blind logic of capital moving mountains to satisfy every conceivable desire that could ever arise in a pony’s mind. How utopian!

Very well, Mr. Economist. We will repeat our tale with a new protagonist.

This is you now.

You are an omniscient and immortal demon from Tartarus with a single-minded dedication to exactly one particular goal: you want to maximize utility among the ponies of Equestria. In achieving this task you are provided with everything availed to the paperclip demon.

Your utility function is much more complex than the paperclip demon’s. This is because your utility function is derived from the individual utility functions of everypony in Equestria, aggregated together according to some rule. The most parsimonious rule is the utilitarian rule, the one that simply adds up the utilities of each individual and seeks to maximize the total. But popular among negative utilitarians is the leximin rule, the rule which seeks to maximize the lowest utility held by any individual, then the second lowest utility, and so on, the point being to prioritize the alleviation of the most severe suffering before anything else. We will begin our analysis by assuming you the utility demon are obeying this rule, because it will result in a less messy analysis. Then we will examine the changes in distribution from moving to the utilitarian rule.

Your very first priority is to distribute goods and services to the worst-off ponies in society. The homeless, the starving, the sick, the freezing. For this you need to pay farmers to grow food, construction workers to make houses, and all the other myriad things that ponies need to fulfill their needs. This list is actually more or less identical to the list of things that the paperclip demon made to incentivize his workers to make paperclips, but while the paperclip demon was only satisfying the desires of ponies as a means, you are doing it as an end.

Like the paperclip demon, or any demon, you can’t provide any of these valuable things unless you have a productive class to produce a surplus for you to distribute. But the rewards of this productive class will be considerably nicer than they were under the paperclip demon. The paperclip demon could simply threaten to starve anypony who didn’t work. Enough money for cheap food, water, and housing was enough to incentivize ponies to make paperclips. You are unwilling to use the same tactics, since the whole point of your utility function is that you think it’s bad when ponies starve. In order to incentivize ponies to produce, you need more enticing things. Since you are maximizing the lowest utility function in your society, you do not like inequality. You do not care directly about the consumption of wealthy ponies the way you do about the consumption of poorer ponies. But just like apples produce paperclips, opera tickets produce apples. The fundamental structure of your distribution is the same as that of the paperclip demon: money exits the pile to a productive class which sends a greater amount of money back to the pile, at the rate which maximizes the amount which can be sent to the non-productive class. The only important difference is that higher standards of living raise the opportunity cost of working, and therefore raise wages. Unlike in the P-maximizing economy, the U-maximizing economy must have wages that rise as productivity increases.

I must clarify, in case you have forgotten, the meaning of the “productive class” and “non-productive class”. Because the utility demon is distributing resources to all ponies, this includes the ones who do not provide labor to the utility demon, because of disability, age, injury, or simple unwillingness. You might be imagining the ponies who provide labor to the utility demon as the “productive class”, and these other ponies as the “non-productive class”, but remember that I coined these phrases to refer not to working ponies and non-working ponies, but to ponies who produced consumer goods and ponies who produced paperclips. In this case, the “non-productive class” consist of the ponies who work to produce the goods distributed to maximize U rather than to add profit to the pile. That is, the non-productive class consists of the doctors, farmers, scientists who invent vaccines, and the like. The productive class on the other hoof consists of the exploited ponies who generate the surplus that pays the non-productive class: celebrities, luxury fashion designers, and professional buckball players.

This may be as good a time as any to defend hedonism from its most prominent enemy in the sphere of political economy: desertism. If the utilitarian’s rule is “to each according to his need”, then the desertist’s is “to each according to his contribution.” To many, it just seems intuitively fair that resources be distributed to those who have contributed the most. The idea comes in left-wing and right-wing flavors, but they are all incoherent, and the previous paragraph should help you understand why.

If “contribution” is defined as bringing money into the pile by performing profitable work, then the doctors and scientists under the utility demon are not contributing, and therefore deserve no payment. But the fashion designers and buckball players are contributing loads, and should be paid much more. If “contribution” is defined in some other way, then the question is… how? Did the paperclip workers under the paperclip demon deserve their pay? Do all workers deserve to be paid for their work? What if somepony spends all day making mud pies on the side of the road that nopony wants? Do they deserve to be paid for that? The left-desertist answer tends to be that all work deserves pay in proportion to how hard they worked, unless it’s work that the left-desertist doesn’t like, in which case it doesn’t count. Artists deserve pay for their contribution, unless the left-desertist doesn’t like them. Mothers deserve pay for raising their kids, but fathers do not. The mud pie maker doesn’t deserve pay, and depending on the left-desertist, managers, actuaries, and stock traders might not either.

The right-desertist is likely to define contribution as profitable labor. This is because the right-desertist is eager to justify factor payments under capitalism as being legitimate and transfer payments as being illegitimate. Libertarians get very angry when people receive money without creating profit for someone. Liz Wolfe, journalist at libertarian magazine Reason, recently went to twitter with an angry tirade against an article by the Ethicist about a painter with a part time job who uses the SNAP program to purchase food. Liz asks, incredulously, “how could they possibly think is this okay?” It turns out the Ethicist is a desertist as well, but of a more left flavor. Their response is that the painter is contributing to society by creating art, and the food she receives from SNAP should be considered payment for her art. Liz Wolfe says:

“I suppose I am just speaking for myself, not EVERYONE IN SOCIETY, but I would much rather this person get a real job vs. pursuing her amateur art, and stop using the money provided by actual working taxpayers to pay for her gotdamn sweetgreen.”

Presumably she would also rather the doctors in the NHS get real jobs instead of using taxpayer money to pay for their chip butties.

The right-desertist might be, and often is, tempted to say that the two situations are distinct. Of course doctors contribute more than artists, because even though neither might produce profit, the former WOULD produce profit in a laissez-faire society where healthcare was completely privatized. This argument has an alarming circularity when viewed in full context. Laissez-faire is good because it distributes resources to those who deserve them. What does someone deserve? Whatever would be distributed to them under laissez-faire! The argument assumes as a premise the same thing it’s supposed to be arguing for.

Libertarian darling, F.A. Hayek, says:

“In a free system, it is neither desirable nor practicable that material rewards should be made generally to correspond to what men recognize as merit, and… an individual’s position should not necessarily depend on the views that his fellows hold about the merit he has acquired.”

But that has not stopped generations of libertarians from justifying their system under the grounds that it distributes according to merit (and therefore, that any distribution which would not happen under their system must be undeserved).

The utilitarian has his own reasons for desiring that hungry people should eat food. He has no need to defend a person’s use of food stamps on the grounds that they are being paid for drawing supernatural fanart. The distribution is justified because it’s a distribution that satisfies needs. Just like the paperclip demon before him, the utility demon is only interested in compensating labor as a means, not as an ends. When the effective altruist donates to charity, he wishes to donate to where his money can fulfill the greatest need. He does not donate to the hardest workers. There are no effective desertists.

Moving on. We are now ready to make the final alteration to our thought experiment. We will swap out the utility demon’s leximin social welfare function with the utiliarian social welfare function. You now inherently value all pony utility, rather than simply maximizing the lowest utility function in Equestria. This means that the distinction between the productive and non-productive classes is now extremely blurry. All resources created to incentivize workers now also double as resources that increase U directly. If we had started with this particular demon, it would be more difficult for the reader to see that the underlying structure of the distribution remains the same as the previous examples. Just as the paperclip demon’s economy was separated into a production-for-profit sector and a production-for-paperclips sector, the utility demon’s economy is separated into a production-for-profit sector and production-for-use sector. It just so happens that the latter sector now contains the former. All production-for-profit is production-for-use (with some notable exceptions we’ll examine later), but this does not go both ways! Not all production-for-use is profitable! Your rate of exploitation is lower under the utilitarian function than it was for the leximin function, but it is still quite high, with its exact value varying by the pony, and depending on how much low-hanging utility fruit exists outside of the workforce. If you increase the number of bits in the pile by one, that extra bit will increase the value of U no matter what pony you give it to, but it will not raise the value of U equally for each potential recipient. Ponies who already have less money will benefit more from one additional bit than ponies who already have a lot. For a homeless pony, one bit can make a huge difference to her day. For a millionaire pony, she will not notice it. This is called the principle of diminishing marginal utility. The pure production-for-use sector will therefore distribute resources in basically the same way as it did under the leximin function, because for either social welfare function, the optimal strategy is to provide resources to the worst off first. The only difference is that the pure production-for-use sector will be smaller under the utilitarian function, and therefore the utility floor of Equestria will be lower.

You can understand this by imagining you the demon making the change from one social welfare function to another. You start out distributing according to the leximin function, and then you suddenly have a change of heart and want to change the distribution to satisfy the utilitarian function. You examine the quantity of bits leaving the pile towards the production-for-use sector. If you reduce it by ten, you have another ten bits you could send towards the production-for-profit sector. If you do that, you will receive nine bits back, which you can send to the production-for-use sector. The one bit taken away from the production-for-use sector results in a loss of 2 utils. The ten bits added to the production-for-profit sector result in a gain of 6 utils. The redistribution of bits results in a higher value for U, so you should lower the rate of exploitation below the profit-maximizing rate and redistribute the ten bits. Then you should repeat the process until the utility floor has been lowered to the point where any redistribution from the production-for-use sector to the production-for-profit sector will either lower or remain constant the value of U. But the utility floor will still exist, because below a certain rate of exploitation, directly optimizing for utility rather than for profit will always be a superior strategy.

Wow! That sure was a lot of words! What did we learn? Well, we learned that the leximin and utilitarian social welfare functions are no different from any other social welfare function. Any coherent preference ordering of possible world-states can be expressed as a social welfare function, and for every possible social welfare function, there exists, somewhere in Meinong’s jungle, a demon which can outperform an optimal market in maximizing it. There is only one exception to this: the social welfare function corresponding to the exact distribution of resources achieved by an optimal market. I will call this the economistic utility function, as it is the implied value system of many economic models.

Thus, apart from the given exception, it is always possible, and usually trivial, to invent a distortion of the optimal market that will result in a superior outcome according to an arbitrarily chosen social welfare function. The paperclip imp must simply ask “what would the paperclip demon do?” before he intervenes into the market to increase P. The utility imp must ask “what would the utility demon do?” before doing the same. He can be confident that leaving the free market alone to do its thing is not guaranteed to produce optimal outcomes.

We now have a model we can use to think about misalignment. If the market does something that the utility demon would not do, it’s misaligned.

Misalignments generally fall into two major categories: Inequality, and goodharting. Inequality refers to the market’s overwhelming bias for satisfying the desires of some moral patients over others. Goodharting refers to occasions when production-for-profit does not increase U at all.

Inequality is an obvious misalignment. So much so that it’s the one everyone notices. It’s not difficult to look out the window and see that some people have three houses and some zero. It’s hard to be convinced that this is an ideal distribution of resources. Besides the obvious “distributive inefficiency” as Abba Lerner would call it, there are also dozens of more abstract downsides to inequality which I will not go over here. Many have raised objections to the widely held belief that inequality is bad. These objections are weak. Most of these objections are from confused right-desertists, deontologists with very stubborn views on property rights, or temporarily-embarassed egoists, but I will give a brief response to the arguments given against egalitarianism from a utilitarian point of view. These usually go something like this:

“The economy is not zero-sum. Whether or not someone else is rich has nothing to do with whether you are poor. It’s possible for greater inequality to actually be better for the poor, because it could result in a greater amount of total wealth in society than would exist otherwise.”

This is a common argument. Ludwig Von Mises uses it against Karl Marx (who was not even an egalitarian by the way) in this rap battle funded by the Charles Koch Foundation.

“The pie can get bigger. It’s not zero-sum. Free markets have lifted the lowest incomes.”

Anarcho-capitalist Bryan Caplan invites us to imagine a world where there is a 100% tax on everything, the proceeds of which are distributed equally among the population. He mostly thinks this is just a big violation of negative liberty, but he also clearly wants to emphasize the bad consequences of such a policy:

“Given these awful incentives, everyone would have to survive on an equal share of virtually zero output.”

It’s true that the economy is not zero-sum, and it’s true that this implies some degree of inequality is necessary, just as it implied for the paperclip demon that some degree of non-paperclip production was necessary. Apples create paperclips after all, so it’s theoretically possible that Jeff Bezos’s spaceship creates rice for Haitians. Bryan Caplan is correct that the utility demon would not set the rate of exploitation at 100%. But an anarcho-capitalist doesn’t need to prove merely that the ideal rate would be under 100%. They need to prove that it would be 0%! The fact that some inequality is necessary does not in any way demonstrate that the current level of inequality is not too high. As for Mises’s point, he could just as easily say the same thing to the paperclip demon.

“Two hundred years ago, there were no paperclips in all of Equestria. Now, thanks to capitalism, free markets have provided us with millions of paperclips! You may see ponies building big statues and skyscrapers made with metal and think that they are trading off against paperclip production, but statue production and paperclip production are positively correlated, not negatively!”

But clearly, big metal statues do trade off with paperclips, unless they are necessary to incentivize the creation of more paperclips, which is unlikely. Any bits that the paperclip demon sends to the statue-builders are bits that he could have sent to the paperclip workers. It is not impossible that going to space might have incentivized Jeff Bezos to improve amazon in such a way that it somehow improved life for people in Haiti, but there is no economic reason to believe this to be the case, and it seems unbelievably unlikely. It is unwarranted faith that the market is accidentally optimizing for something it is not trying to optimize for.

We have shown that it is possible for the level of inequality to be either above or below the U-maximizing rate. So, if you’re a utility imp who wants to know whether his society is too unequal or not unequal enough, here is a handy technique for figuring out what kind of world you live in: be an effective altruist.

If you do the effective altruism thing, and you and all your buddies get together to figure out what the most U-maximizing uses of a dollar are, and you live in a world where inequality is too high, your answers will look something like:

If, however, you live in a world where inequality is too low, your answers will look something like:

Subsidizing the capital incomes of stockholders

Subsidizing the bonuses of CEO’s

Subsidizing the incomes of business executives

I will leave it as an exercise for the reader to determine what kind of world they live in.

It is impossible for a citizen of the utility demon’s Equestria to be an effective altruist, because they would never have been distributed anything in the first place unless it was already being put to best use in their hooves.

Goodharting is what people are usually talking about when they talk about markets being misaligned. From the hedonistic perspective (which, if you have not been able to tell, is the perspective I take), the profit motive actually has a tendency to do pretty well at incentivizing U-increasing behavior. The logic of production for exchange is that it incentivizes the production of things that people are willing to trade money for, which tend to be good things. This is why markets have created so many cookies and video games and stuffed animals and all sorts of very fun things. If you have a more anti-consumerist value system, you may not consider this a virtue, but when I speak of goodharting, I’m talking about situations where “producing things that people are willing to trade money for” is not equivalent to “producing things that increase the amount of pleasure in the world”. Inequality results in inefficient increases in U, but goodharting results in incentives for behavior which do not improve the world even a little bit, and even make it much worse. The most noticeable example of this kind of misalignment is advertising.

I hate ads. They are literal gigantic neon signs plastered all over the planet Earth proudly displaying humanity’s enslavement to the monster machine of capital. The first advertisement that ever went up should have resulted in a public execution, and there should never have been a second one. In 2023, the United States spent 733 billion dollars creating ads. The utility demon would not have done this.

If you are a profit imp who owns a company, your utility function is directly tied to the utility function of “make things that people desire”. If you are in competition with another profit imp, you will both compete to maximize the desirability of your products. You can do this by making your products better, which is a good thing for the economy to incentivize people to do. But you can also cheat, by, instead of making your products better, increasing the desire of the consumer base. Rather than solely working to satisfy the needs of people, corporations are incentivized to create new needs in people! It’s possible for a company to be out-competed by a company that makes worse products, just because the latter had better marketing.

Advertisements are the most noticeable example of goodharting, but they are not even close to the most harmful. Every utilitarian calculation, every examination of the good and evil caused by mankind, every single analysis of whether things have gotten worse or better over time, are all overwhelmed by the fact that an almost unnoticed market misalignment in the middle of the 20th century resulted in the ongoing moral catastrophe of factory farming.

The utility demon would be extraordinarily hesitant to raise a pig for slaughter and consumption (the leximin demon would never do it at all). The consumer’s effect on U would be almost nonexistent compared to the pig’s effect. If it absolutely had to do so, it would probably contribute an awful lot of resources towards the pig’s wellbeing. Pigs are social animals, who are most comfortable in small groups, so the utility demon would likely raise them in such groups, as they live in the wild. They prefer to root around in the soil for food, eating roots and stems, and the utility demon would provide the groups with large ranges around which to scavenge. It would protect them from predation, treat any medical issues, preferably before they arose, and provide them with ample opportunities to engage in their natural behaviors.

None of this is the most profitable way to raise pigs, and so it is not how they are raised in our world. Female pigs are artificially inseminated and kept inside gestation crates, cages which are too small for the pigs inside them to move or turn around. This is done to prevent the mother from accidentally crushing her children because of how cramped the conditions are. A pig’s natural instinct is to create a nest for her babies out of foraged twigs and leaves. Kept in the gestation crate, she is obviously unable to do so. In the wild she would nurse her piglets until they are about three months old, but in the factory farm her piglets are taken away from her at only three weeks. Like for all mammals, separation from her children is a very traumatic experience.

Her male children begin their lives by being castrated without anesthetic. This is because meat from castrated pigs has a more palatable taste and smell, and anesthetic isn’t free, so this behavior is incentivized in farmers. Because pigs evolved to live freely as scavengers in large ranges and small intimate social groups, the extreme crowding of the factory farm creates intense stress in the pigs for their entire lives, leading them to perform compulsive behaviors including biting their own tails. To prevent this, farmers cut off their tails. Again, anesthetic isn’t free, so there is a negative incentive against using it. The tail is not the final mutilation the pig will endure before death, because most farms will also cut off part of each pig’s ear to distinguish it from the others, which is useful to the farm when there are so many pigs in such a small space, and baby pigs will have their teeth cut off to prevent them from growing tusks later. At the age of six months old, when a wild pig would still be a baby, they are carted off to the slaughterhouse. The trip can be very long, and no food or water is provided to them. The crowding in the trucks is so severe that they cannot sit or lie down to rest. There is no space.

124 million pigs are slaughtered in the USA every year. Most of them are stunned unconscious before their throats are slit and they are dipped into boiling water. The system is imperfect (they are only stunned at all because of a regulation from 1958), and some of them are improperly stunned, dying either from blood loss, choking on hot steam, or simply boiling to death. Conditions are even worse for chickens (the 1958 regulation doesn't apply to them), among whom more than 8 billion are slaughtered a year in the USA alone. The scale of this atrocity is unimaginable, and it owes its existence to mundane incentives to meet consumer demand.

So far I have only described a model with which to analyze problems, but the point is to solve them. Putting an omniscient utility demon in charge of all of the world’s wealth is not a viable solution, because omniscient utility demons do not exist.

To my eyes, goodharting seems much simpler to resolve than inequality. It is unquestionably a larger problem by a significant margin, but I think it would be easier to resolve. The law could end factory farming tomorrow. Just make torturing animals illegal. Before then, even moderate regulations, corporate activism, and consumer movements can drastically reduce the suffering of farmed animals. Donations to the humane league are the best use of money I have ever discovered, and since I got my first job I’ve donated ten percent of my pre-tax income to them. As for advertising, the totalitarian in me kind of just wants to make that illegal too, but a more moderate solution might be a marketing tax.

Inequality is the more interesting problem, and solutions come in two forms: redistribution and predistribution. Redistribution refers to interventions in the market that reduce inequality, mainly through taxes and transfers. Predistribution (the way I use the term here) refers to changing the rules underlying the market in the first place to change the market’s optimal distribution. We will begin by talking about redistribution.

One of many reasons why a planned economy is a poor idea is simply that it is unnecessary. It’s a solution in search of a problem. Every demon and imp, no matter their utility function, has their interests aligned with a production-for-profit sector that generates surplus for consumption. This is the same process which creates profit imps. Shareholders and CEO’s all have their own utility functions which lead them to produce for exchange. They have no more intrinsic interest in profit than the paperclip demon does, but they share his instrumental interest in production for exchange. The market can therefore be expected to reliably create incentives, because all of the imps who coordinate its distribution have an individual instrumental interest in doing so. The market, under the right conditions, can replicate to an impressive degree the production-for-profit sector of the utility-demonic economy. The production-for-use sector can be replicated by the welfare state.

The key to designing a good welfare state is to keep in mind what you’re actually doing. The purpose of the welfare state should be to provide for the wellbeing of society to the greatest extent possible given the resources at your disposal. It does not exist merely to correct market failures (although it can do that in some cases) nor to serve as a blue shell to give the disadvantaged a leg up (although it can do that in some cases). It should be THE primary mechanism in society for providing people with what they need. The welfare state is incredibly important. It should provide everybody with as much of the wealth of society as is feasible. The perfect welfare state is one that takes its first dollar out of the least useful money stream and puts it into the most useful money stream, and then repeats the process until all money streams equalize in utility. This means that taxes should prioritize the least valuable dollars, and transfers should prioritize the most valuable uses of money. To this end, welfare state policy should strive to meet the following criteria:

Welfare state benefits should be universal, unconditional, and equal, except when there exists an inequality of needs (for example, disabled people should receive more from the welfare state than abled people)

The welfare state should, whenever possible, prefer direct cash transfers to in-kind transfers

The welfare state should prefer direct benefits to indirect benefits

All economic rents (payments that do not incentivize the creation of more wealth) should go the welfare state with no exceptions

The tax system should prefer taxes on the rich to taxes on the poor

The tax system should prefer taxes with lower deadweight loss to ones with higher deadweight loss

In other words, there should be a utility floor, a minimum level of comfort, below which nobody must ever fall, which is as high as feasible, and grows continuously.

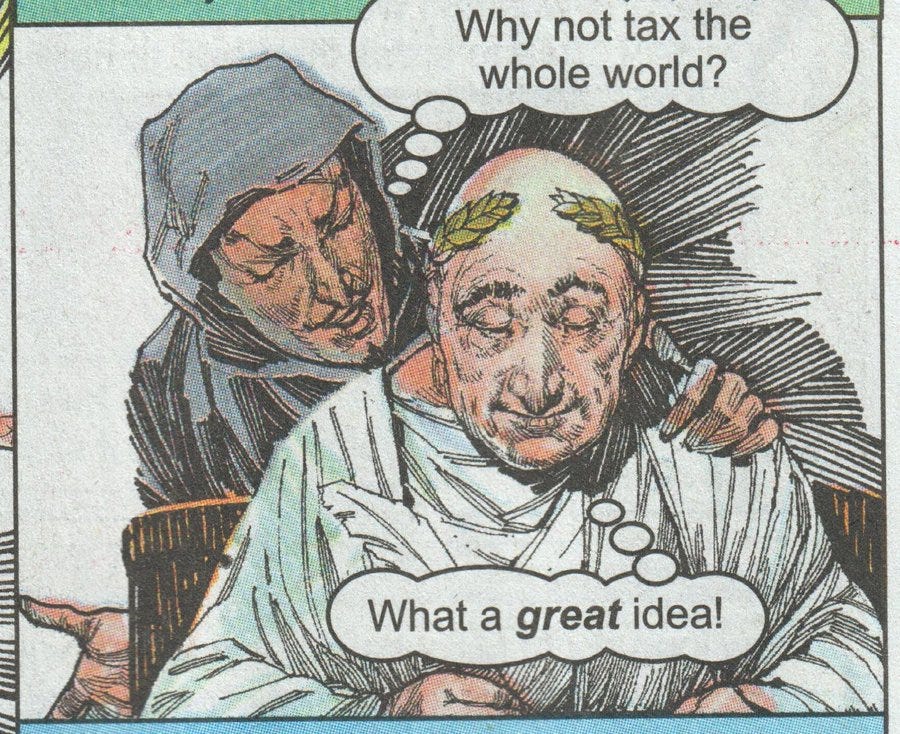

The welfare state should be all-encompassing, and I mean that in the most significant possible sense. Ideally, there would be one welfare state for all sentient beings. A one world government is deeply unpopular, but there is literally no benefit to sectioning off the world into separate nationstates with their own separate tax and transfer systems. There should be freedom of movement all across the Earth, free trade all across the Earth, and one shared tax system and welfare state all across the Earth. Dividing the world’s wealth into highly unequal sections and forbidding equalization between them would never have been seriously suggested if the world economy was being created from scratch, but reinforcing this exact situation is one of the most popular political beliefs on Earth. Remember that Marx Vs. Mises rap battle I mentioned earlier? Well, here’s the line that came right after the one I quoted:

“If you really want to help out the poorest nations, encourage peace, trade, and immigration!”

This is, I will concede, a great point. All three of these things would indeed reduce global inequality and poverty by a huge degree, while also being pareto improvements (and therefore palatable to libertarians). The reason they are so unpopular is because of the brain virus of nationalism: the idea that moral patienthood is determined by geography.

You may have noticed my use of the term “sentient beings” rather than “humans”. This was not a mistake. I think the welfare state should support animals, including wild animals. I have no suggestions for how this ought to be carried out in a rational manner. Feasible wild animal welfare improving interventions are difficult to discover. I only want to give my support for it on principle. Wild animal suffering is a real and large-scale problem, made no less serious by its predating human civilization, and if future humans are able to alleviate it effectively, I think the state will be obligated to do so, as the private sector will have no incentive to do it.

Before I move on to predistribution, I want to make the case for one more unintuitive aspect of the principle of universality, that being that welfare benefits should not be means-tested, meaning that even rich people should receive welfare benefits. Common objections to this are confused, and can easily be resolved by looking at the money distribution like a demon, and not like a tax collector. Benefits that cut off at a certain income level are distributionally equivalent to a tax on the income bracket directly above that cutoff. As such, they violate the principle of progressivity in taxation, disguising a tax on the working poor as a tax cut.

Taxes and transfers are just one way to improve the distribution of resources. The other is to change who owns what in the first place, and therefore change the market’s “fair” compensation. Profit imps are incentivized to distribute money to those who contribute productive assets to the firm, therefore producing more than what it costs to procure their contribution. What is often overlooked is that what each individual has to “contribute” depends on the property norms underlying the market. If redistribution is carried out by exo-capitalist institutions that intervene in the market, then predistribution is carried out by endo-capitalist institutions that determine the rules by which the market operates in the first place, and these are by no means fixed.

There are three factors of production (actually four, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves): Land, labor, and capital. Because these kinds of goods are factor goods, and not consumer goods, they can create new wealth, and markets involving them are not zero-sum. Linen coats may fall apart over time, but the total amount of linen coats in Equestria can increase because there is a steady supply of factor goods. The market prices these goods accordingly and provides income to their owners. Contra the desertist, the market is not paying the owners for the value of their merit, but for the value of their property. They will not relinquish the valuable thing they own unless they are paid for it. This is an important distinction, because the ownership of land, the ownership of labor, and the ownership of capital are all very different in important ways, even if factor payments for all three function in essentially the same way.

In many languages, there is a distinction between inalienable and alienable possession. Inalienable property is that which cannot be taken from you, because it intrinsically belongs to you, such as your arm, your mother, or your opinions. Alienable property is that which could in theory belong to someone else, such as your house, your toothbrush, and your lunchbox. Labor is unique among the three factors of production in that it is inalienable. The distribution of labor-power among the population is unequal not (entirely) because of historical injustices, but because people are fundamentally different from each other, and these differences mean that not everybody’s labor-power will be valued the same by the market. Some people are more skilled than others, and some people’s skills are more profitable than others, because nature played a pivotal role in distributing these skills, and nature is fascist. Land and capital are quite different. They are alienable.

The idea that people are compensated for what they own rather than necessarily what they do is infrequently understood. Many people, even very smart people, seem to be under the impression that all income is labor income. @raginrayguns says:

“A worker and an owner in a factory both rely on reason. But the owner is contributing more, since they contributed the plan for the factory.”

Raginrayguns seems to be confusing owners with industrial engineers. The person who draws up the plan for a factory is paid a labor income for his work. He’s still a worker. It may so happen that he also owns equity in the company which owns the factory, and earns capital gains on that equity, but if he does, those capital gains are not payment for his labor, but payment for his share of the company. The same share would pay the same dividends to anyone who owned it, regardless of whether they contributed labor to the company or not. The more common mistake is to confuse capital income with the labor incomes of money managers and business executives, which is incorrect for exactly the same reasons the former mistake was incorrect. Not all income is labor income. It should be noted that this category of errors is particularly common among right-desertists, who have strong incentives to hallucinate correlations between income and personal merit.

Because a large portion of income in society (about one third, according to Piketty) comes from land and capital, and not labor, it is clearly highly desirable to equalize the distribution of land and capital ownership across society, if such a distribution could preserve the efficient allocation of resources towards production-for-profit. This is the driving motivation behind socialism: the idea that non-labor productive assets should be owned collectively by society as a whole rather than individuals. Because land and capital are very different, the processes by which society might socialize land and capital are also very different, and we will examine them separately.

Land is the easy one. For starters, land income is an easier concept to understand than capital income, which tends to make people search for invisible labor. If you own land, people have to pay you for the right to use that land. Using your land can create more wealth, so you own a productive asset which earns you continuous income. Businesses need your land to make money, so they’re willing to pay in exchange for the value provided by your land, paying you rent. If your land happens to be particularly valuable, this rent will happen to be particularly large. If you buy a sandwich in New York City for twenty dollars, about ten of those dollars will go to whoever owns the land the sandwich shop is on, because New York land is more valuable than land elsewhere, but New York bread and chickpeas and tomatoes are not. If land were not priced, then either nobody could be granted exclusive rights to land, and therefore could not use land for productive purposes, or all of the land would be owned by people with no incentive whatsoever to give it up. Either way, land would not be allocated towards its most productive uses. The lack of property rights around land would constitute a market failure in the land market, and the state would have to intervene to establish property rights allowing land to be priced, resolving the market failure. However, the fact that is valuable for land to be priced does not mean that anyone actually needs to be paid that price. The law could demand that all land rent be burned instead of paid, and land would still be allocated just as efficiently as it was before. Land is allocated towards its most productive uses because it’s allocated to those willing to pay the most for it, and therefore those who are expected to make the most money with it. It’s the paying part that is important, not the receiving part.

Because of this, socializing land is very easy. All land could be owned collectively, and the state could rent it out on the people’s behalf. Individuals could be granted exclusive usage rights over this land, but only if they pay rent to society for the privilege. When you do socialism for land, it’s called georgism, and it’s often described not as collective ownership of land, but as a tax on the value of land minus improvements (the stuff on top of the land isn’t collectively owned, obviously), a tax which just so happens to be at the rate of 100%, which pays for a universal basic income. This is an equally valid analysis, and I could have defended such a system without reference to property at all, merely on the basis of 4th rule for welfare states, as land rent doesn’t incentivize the creation of more wealth, but I think the description of socialized land as a tax and transfer disguises the radicalism of the policy. It is not merely a tax shift, it is the complete liquidation of an entire economic class, landlords.

Socializing capital is much harder. Capital income is not rent. Paying land income does not incentivize the creation of more land, but paying capital income does incentivize the creation of more capital.

Capital is wealth that produces more wealth. Karl Marx describes it as undead labor: stuff that was produced by labor which can produce more stuff. A machine that cuts potatoes into french fries is capital. The factory that machine is in is capital. The software the machine runs is capital. If you happen to own a privately held company, then you own the capital the company holds, and receive capital income from them as profit. If you buy a share in a publicly traded company, then you own a portion of the capital that company holds, and receive capital income from that portion as dividends and capital gains. If you are a bank, and you loan money out to a business, you are providing capital to that business (or, more specifically, money which represents and can be exchanged for specific capital goods), and will receive back payment for your contribution as interest. When you purchase stocks, bonds, or securities from a capital market, you are providing capital to a business, and, if you have allocated that capital to a profitable use, you will be paid your contribution, and paid more the more profitable your allocation. Despite the CMC’s protestations, this is analogous to a labor market, where owners of labor-power are also incentivized to allocate their labor-power to its most valuable use. Labor is not unique in its capacity to produce wealth. After all, humans can be viewed as machines with ownership rights over themselves.

It’s clear that capital differs from land in an important way. If you tax land income at a rate of 100%, the amount of land in the world will remain the same. If you tax capital income at a rate of 100%, society would soon find itself with much less capital. Land cannot be created, so giving money to its owners does not incentivize the creation of new land. Giving money to owners of capital and labor, however, does incentivize the creation of new capital and labor. So the solution for land does not work as a solution for capital. There must be an incentive to invest money into profitable firms rather than spending it on consumption. The task for the wannabe socialist then, is to find a way to create a more equal distribution of capital ownership while preserving this incentive.

Of course, the government can just invest in the stock market like anybody else, and use the dividends it earns to pay for things. If the government owns a large investment fund, it’s called a social wealth fund. In Norway, one of the most equal countries in the world, there is a titanic social wealth fund funded by revenue from the state-owned oil company. This fund, called the oljefondet (oil fund), owns 1.5% of all publicly traded capital on Earth. Alaska has a similar fund called the Alaska permanent fund, also funded by oil revenue, which is held in common by every citizen of Alaska and paid out to each of them as a dividend every year. The government could also replace the corporate income tax with a one-time mandatory share issuance, acquiring some percentage of all the corporations in its jurisdiction. Metaphysiocrat says that a social wealth fund can also be funded by quantitative easing.

The social wealth fund idea has done quite well for itself in practice, but a more revolutionary-minded socialist might be disappointed by it. It doesn’t scale up to the whole of the economy. The oljefondet can’t own 100% of the capital on Earth. If it did, who could it sell it to? If the whole capital stock of the world were owned by a social wealth fund, there could be no capital market, and therefore capital could not be priced, and could not be allocated towards its most efficient uses.

An alternative proposal is to have a market economy consisting not of privately held and publicly traded corporations, but entirely of producer co-operatives, where the workers in the firm would own it. Rather than a stock market, co-operatives could raise capital by selling bonds to co-operative credit unions and/or a public bank in the debt market. This is one of the oldest and simplest proposed socialist systems, going back to the early 19th century. Its main advantage is that it preserves competition, capital markets, and the profit motive, while creating a much more equal distribution of capital. Some anarchists, specifically mutualists and left-wing market anarchists, are fond of this idea because it lacks economic classes, which are a form of hierarchy. It’s not as egalitarian as the utility demon’s distribution, since capital income accrues to workers rather than everybody, and, as Matt Bruenig points out, the ratio of capital to labor income (sometimes called the Marx Ratio) varies widely by industry, meaning that such a system could exacerbate inequalities between workers in capital-intensive and non-capital-intensive industries. However, it would still be significantly more equal than a society with private ownership of capital, and wealth inequality like what you see in America today would be impossible to arise in the first place. Also, I believe that inequalities in Marx ratios between industries would be much less severe in a society with a land value tax, since the industries with the highest Marx ratios are uniformly the ones which earn money through land rent. Real estate investment trusts have absurdly high Marx ratios compared to other kinds of firms. The co-operative system also has other benefits, most surprisingly that co-operatives tend to be more efficient than privately owned firms. This may result from the fact that workers in co-operatives are directly, rather than indirectly, incentivized to maximize the shareholder value they produce, because they are the shareholders. Co-operatives are also frequently argued for on democratic and communitarian grounds.

“Now you wait just a gosh dang minute here!” says Applebloom. “Profit motive? Stock markets? Maximizing shareholder value? This doesn’t sound like real socialism at all!”

Well-disciplined utility imps like myself have no intrinsic preference for real socialism over fake socialism. My only preference is for good socialism over bad socialism, and if the socialism produces better outcomes which maintains capital markets and the profit motive, then so much for real socialism.

“I don’t think you understand what the problem with capitalism actually is!” says Sweetie Belle. “This is the difference between liberals like you and real socialists. The liberal criticism of capitalism is that it’s not efficient enough! You merely complain that the distribution of money isn’t equal enough, and it doesn’t even occur to you that some ponies might not like their lives to be ruled by money at all! Socialism is not about efficiency or equality, it’s about humanity! Or, um… equinity? Socialism is when wage labor itself is done away with, not when capitalists share their profits with everypony! Do you really want to spend your whole life toiling away for money, even in your perfect utilitarian technocrat utopia?”

Money is nothing but a store of value, a signifier which represents real wealth, which is what actually rules people’s lives, and always has, since long before capitalism existed. Before men and ponies were tyrannized by money, they were tyrannized by the soil. Before any economy even existed, prehistoric hunter-gatherers were tyrannized by the meager provisions of mother nature, which demanded the total subservience of their lives to the pursuit of the means of subsistence. If money ceased to exist, this tyranny would still remain. Its origin is scarcity, not the abstract representation of scarcity. As long as labor is necessary to produce the wealth that society relies on, workers will need to get paid, and that means there must be a labor market.

Which brings me to my final point. The status of labor as a commodity, with all its attendant miseries and evils, can only be abolished in a world where labor ceases to be necessary as a factor of production. If all labor were to be automated, humanity could not only be freed from work, but also from inequality. All wealth would derive from capital and land, which could be held collectively. If labor were all automated, capital allocation could of course be automated as well.

Remember much earlier, when I stated the first theorem of welfare economics? I’ll remind you: if all goods are distributed according to optimal market conditions, the distribution will be pareto optimal, meaning that no further improvements can be made to any individual’s utility function unless someone else’s utility function is reduced. Now it is time for you to hear the second theorem of welfare economics: Any pareto optimal distribution can be achieved by an optimal market for some given set of initial endowments. This is important because the optima of the utilitarian and leximin functions are pareto optimal, meaning that there exist conditions under which an optimal market would maximize each of them.

All of this is to say that in a fully automated post-work society, there need not any longer remain any meaningful distinction between factor payments and transfer payments, or between production for exchange and production for use. Under perfectly equal conditions, possible in a world where only alienable factors of production are valuable, an optimal market, provided there was no goodharting and individuals made rational purchasing decisions, would be completely aligned with the utilitarian function. There would be no market misalignment whatsoever. Problem solved.